Last night I had the privilege to meet and teach Eddie*, an ESL student from Mexico, at Literacy Advance of Houston. He was there to learn in the “Math and Your Life” class, as part of the “Math and…” class series.

I didn’t realize I was there to learn too.

I walked in prepared to discuss just about anything math related. And I’m glad that was the preparation I did.

Eddie was interested in something that I’ve long struggled with. And I’m guessing many children struggle with it, too.

In English, the number 1600 is pronounced both as sixteen hundred and as one thousand six hundred. I still get these mixed up. Not when I stop and think about them, but when I casually and quickly throw them out.

Husband is often stunned when I tell him I saw a new suburban at the low low price of thirty-five hundred dollars. Of course I mean thirty-five thousand dollars!

It’s not just me, I guess.

I wonder how many other grown-ups still struggle with this. And how often we neglect to teach this to children.

We are quite accustomed, and comfortable, with teaching our youngsters to count from 1 to 10. Were amazingly proud when we can get them to count from 1 to 20.

Is that enough? Based on my conversation with Eddie last night, no.

Teach them skip counting with hundreds!

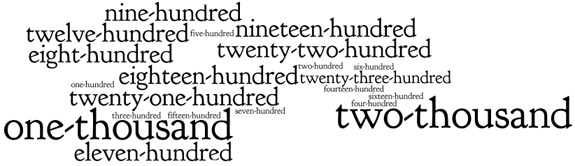

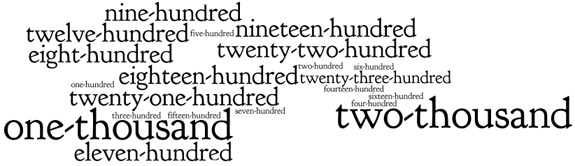

Why not use the 1-20 model with hundreds? Like this:

one hundred

two hundred

three hundred

.

.

.

eight hundred

nine hundred

one thousand

eleven hundred

twelve hundred

thirteen hundred

fourteen hundred

.

.

.

nineteen hundred

two thousand

twenty one hundred

.

.

.

Teach them all sorts of counting!

I suggested in this article to count with your children by fractions. It never occurred to me to count by giant numbers.

What other ways should we teach children to count? Share your ideas in the comments.

*”Eddie” is used as a variable – i.e. his name has been changed because I didn’t ask his permission to talk about him.