My day job colleague told a beautiful story yesterday. He had been washing his car late at night, in the dark, and was approached for assistance. He is generous beyond belief, and apparently he made a real impact.

Oh, and it involved a little math.

I was washing my car the other night and really getting after it. I had the scrubbing brush going and was really making progress on getting the car clean. I was totally focused and I felt a tap on my shoulder. It startled me and I turned around to be faced with a large African-American woman who said, “I’m sorry, I don’t mean to interrupt, but we’re having car problems. Is it possible you can help us? I think we need the battery jumped.”

I looked down the street and saw no other people and no car. Within a split second I remembered my latest purchase: a wireless battery charger that needs no people, no cables and no extra car to jump a battery. I got it out of my garage and handed it to her.

“I’m in the middle of washing my car. Why don’t you borrow this? It should help.”

She thanked me and walked away with the charger. I got back to washing my car.

Five minutes later there was another tap on my shoulder. Another African American woman was standing there holding a five dollar bill. She offered it to me.

“Oh my goodness, no,” I said. “I’m not taking your money. I’m just glad I could help.”

Another 5 minutes went by and I saw one of the ladies put the battery charger close to my garage. I was really getting into the car washing at this point – suds everywhere – so I didn’t pay much attention.

When I was returning my carwash supplies to the garage, I saw a crisp new $100 bill on top of the battery charger!

That thing was only $40 – and they just gave me $100 to borrow it!

This is a wonderful and touching story. These ladies were having difficulty finding someone to help them. Not only did my friend help, he also freely gave them something to use and trusted without question that they would return it.

They, too, were moved by his generosity.

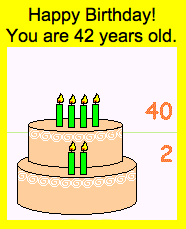

The numbers don’t work.

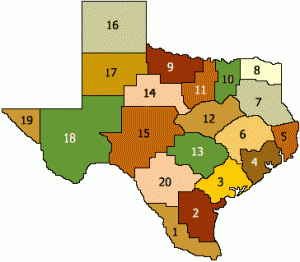

It looks like this:

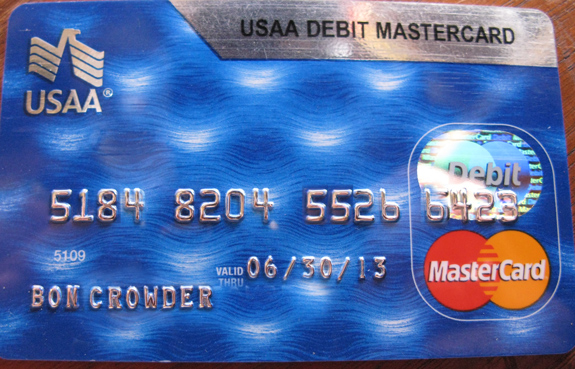

- Battery charger cost: $40

- “Rental fees” offered: $5

- Shown gratitude: $100

The numbers don’t make sense. And in a way they shouldn’t. The $100 bill wasn’t really money. It was the biggest, fattest, loudest thank you note ever written. There’s no value you can place on someone being free and generous and trusting.

It still goes in as $100 in the eyes of the bank. But what do they know?

Notice the math and share the story.

When you share this story, point out the math. Especially if you tell this in front of (or to) children. Making the connection of generosity and emotion to math will help everyone see how integral math is in our lives.

How about you? Do you have a story of generosity that you’re just now realizing involves math? Share it in the comments!