You’ve taught what a function is. And the kids are starting to understand what the domain is all about.

But then they ask, “What’s the point in the range?”

As I wrote in a previous post, a function is a question with only one answer to a valid question. The domain is the set of all valid questions. The range of a function is the set of all answers you can get.

Simple? Sounds like it – but kids the world over still struggle with the question, what’s the point of the range?

To be or not to be a function.

Why is it important to know all the answers of an equation? It has to do with the equation being or not being a function.

If you have an equation like

you have more than one answer per question.

Here are some valid questions associated with this equation:

- What is the square root of a number, specifically the number 1?

- What is the square root of a number, specifically the number 1.69?

- What is the square root of a number, specifically the number 4?

- What is the square root of a number, specifically the number 9?

The answers to these questions are:

- 1 or -1

- 1.3 or -1.3

- 2 or -2

- 3 or -3

Notice that there is not “only one” answer to each question. So this equation isn’t a function!

But that’s no fun at all!

You can force an equation to be a function by limiting the answers.

By limiting the answers (AKA limiting the range of a function) you can force an equation to be a function. So if we write

We have just limited the range of answers to be only the positive square roots of numbers.

The practical application for kids is the graphing.

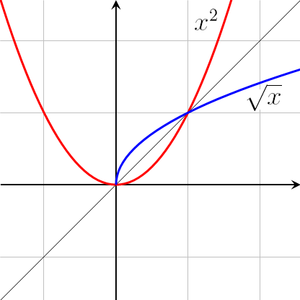

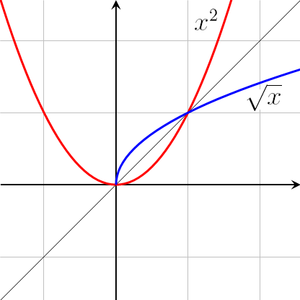

In this image above it’s the blue curve:

You can see that we get only the “upper half” of the curve. If you look at “squishing” a function (like the garbage compactor in the movie Star Wars) you can see the range of a function (all y-values) becomes the vertical line:

The line starts at zero and goes up forever. (In the video it stops, but that’s only because I have a hard time displaying forever on a computer screen.)

The handy thing about knowing the range of a function before you graph is that you know how much space on the paper you need – or how small to make your units!

Does this help? Share your range of experiences with this in the comments! (And pardon the very bad pun.)