Most parents aren’t professional mathematicians. But there are a few. This is the fourth in a series of interviews with mathematician parents with the goal of helping parents integrate math teaching into parenting.

I am honored to be able to interview one of math education’s leading minds, Marilyn Curtain-Phillips, author of Math Attack – How to Reduce Math Anxiety in the Classroom, at Work and in Everyday Personal Use. She also created the amazing playing card deck (also named Math Attack) where the numbers on the numbered cards are tiny expressions – the 4 of diamonds has 22 on it!

MathFour: Thanks so much, Marilyn for sharing some of you time with us. First, I’d like to ask about your background. What is your degree and career? How long have you been in math?

Marilyn: My bachelor of science degree is in mathematics. My master degree is in education with a concentration in mathematics and then an additional 30 hours of mathematics. I have been teaching mathematics for 21 years. I have taught grades 6 through 12. In addition I am now teaching on the college level at a local university for the past three years in the evenings while teaching high school during the day. Prior to teaching, I worked in government and banking for 10 years in the area of accounting.

MathFour: Wow, your life has been so full of math stuff! Tell me about your children. Are any of them more or less interested in math than the other children?

Marilyn: I have two children ages 23 and 18. My son, the oldest, has a degree in graphic design. His interest since elementary school has always been in art. Therefore he never showed an interest in mathematics and it was a bit of a struggle. My daughter has just graduated from high school and is going to college with a major in early childhood education. She has been much stronger in mathematics than her brother. But she doesn’t want to teach mathematics, of which I think she is really capable of.

MathFour: Did you have any worries about your children academically? In particular, did you think they will do better in math than in other subjects because of your influence?

I encourage them to do what they enjoy. I feel they have adequate mathematics skills and a good foundation due to my additional help provided at home. As a high school mathematics teacher, I have grown more concerned at the foundation that students are coming to high school with.

MathFour: How did you play with your kids? Did you incorporate math into your play?

Marilyn: We enjoyed playing board games such as checkers, chess, uno, sorry, playing cards. I wanted to use games that help thinking and reasoning skills. This made great family discussion times while having fun.

MathFour: Do you think you speak with your children or behave differently than other parents because you have a math background?

Marilyn: I have always spoken positively about mathematics. Many parents will say in front of children that they dislike mathematics or is not good at it. To me this almost like telling children that mathematics is something that is tolerated and should be dreaded and avoided whenever possible. As a mathematician I know how much mathematics is a gateway to many

opportunities. This is one of the reasons that I list careers in my book, Math Attack.

MathFour: Have you ever had any of your children express negative thoughts about math and how did you handle it?

Marilyn: Yes, my children have spoken negatively from time to time, mostly during test times. I offer advice and encouragement. It is important to stay positive and listen to their concerns and make suggestions.

MathFour: Have you ever disagreed with one of your children’s math teachers? What happened and how did you handle it?

Marilyn: Yes, I have had a different method of solving math problems. I talked with my children and let them know that many math problems can be done in different ways. Actually I prefer for my children elementary and middle school teachers not know that I am a mathematics teacher. I didn’t want my children to be graded on a tougher standard than other students.

I experienced this growing up in a small town. My mother was a high school mathematics teacher, I felt looking back that I was graded on a tougher level and was expected to be extremely strong in mathematics. My sister experienced this also. She is an artist and doesn’t like mathematics.

MathFour: Now to change direction a little to a more worldview of math. What do you see as the biggest challenge in math education today?

Marilyn: I feel that many students do not have a strong foundation and understanding of mathematics. I have far too many high school students who do not have their times table and or addition facts memorized. Many mathematics textbooks cover too many topics. Studies have shown that the United States textbooks are thicker than other countries that are stronger in mathematics. It almost feels like a cram session.

By the time students get comfortable with a concept it is time to move onto something else. I feel this makes students feel less confident about their mathematics abilities. I think these feelings continue throughout the rest of their adult lives. Which leads to many adults going into careers that require as little mathematics as possible.

MathFour: What do you see great happening in the world of math education?

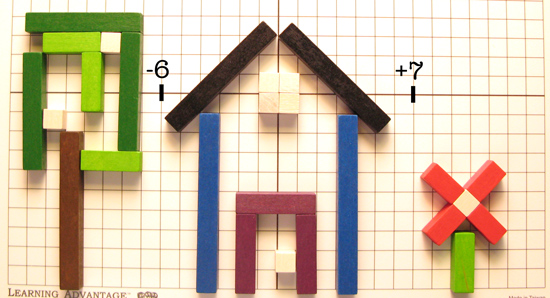

Marilyn: I think that it is good that a more hands on approach to teaching mathematics is now being used. Teachers are teaching to the different learning styles. I think that it is good that more high schools are requiring students to have more mathematics credit before graduating from high school. Many states require students to have three or four credits of high school mathematics. Also many of the mathematics curriculum are teaching with everyday life application.

MathFour: What advice can you give to non-mathematician parents that might help them raise their kids to like and appreciate math.

Marilyn: I would suggest to non-mathematician parents to speak positively about mathematics. Let their children understand that mathematics is like anything else – it takes practice and patience. Just as parents tell their children to practice at playing sports, they should feel that mathematics takes the same time and effort. Also parents should show their children positive ways they use mathematics in everyday activities such as sewing, cooking, planning a family trip, budgeting and grocery shopping.

MathFour: I noticed that you also have a new math workbook Who is This Mathematician/Scientist? Can you share with us a little about it?

Marilyn: It is a workbook for grades 6 through 12, after reading the biography paragraph, students must solve the math problems to see who the bio is about. The activities can also be used as a way to promote multicultural awareness and appreciation.

MathFour: I can’t wait to check it out! Thanks again for your time and sharing with us.

How about You? Got any questions for this week’s mathematician parent? Ask them in the comments and we’ll drag her in here to answer them.

![[50 Word Friday] A Conversation Between Parents After a Homeschool Convention](https://mathfour.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-148.png)