This is a guest post by Dr. Vicki Parker of The Brain Trainer.

If your child has always done well in math but has recently had difficulty in one area of math, such as geometry, then tutoring on specific information may be helpful.

However, if your child has struggled with math year after year, it may be time to look at underlying cognitive skills, the building blocks of thinking. The specific skills that drive math include

- Attention

- Memory

- Visual processing

- Logic and reasoning

- Processing speed

- Number fluency

If there are weaknesses in any of these areas, there will be learning struggles.

Attention is the ability to stay focused over time.

Attention is important for math because you have to be able to focus and attend over time to information, especially as problems get more complex. You can tell if your child has trouble paying attention if he understands the concept of the problem but adds instead of multiplies, or subtracts instead of adds.

A simple deck of playing cards can be magic for reinforcing cognitive skills. To build attentional skills, have your child raise his/her hand or hit a bell whenever s/he sees the targeted number or suite of card as you flip through a deck of playing or Uno ™ cards.

To further challenge your child, s/he must say the targeted card or quickly add, subtract or multiply a number to the card. To build sustained attention, add another deck of cards.

Memory is the ability to store and retrieve information.

Memory is important to recall number facts and sequence. What’s your child’s ability to hold on to the first steps of a problem or the initial calculation?

If she cannot hold this information long enough to move on to the next step of the problem, progression will be difficult. She may need to retrieve previously learned information from long-term memory to execute the problems at hand.

Try showing your child a numbered card, then turning it over, hiding the number, then have your child say the card number. Present another card in the same way.

Next, have your child remember the two numbers and then add the numbers. Repeat this process with two new cards at a time.

As s/he gets better, have him/her work on serially adding in this sequence:

- See 1st number & hide

- See 2nd number & hide

- Add the two numbers

The child will recall last number shown (not the sum), you will show & hide another card and the child will add this new number to the previous number recalled.

Continue, but remember: don’t add the sum number, only the numbers presented visually.

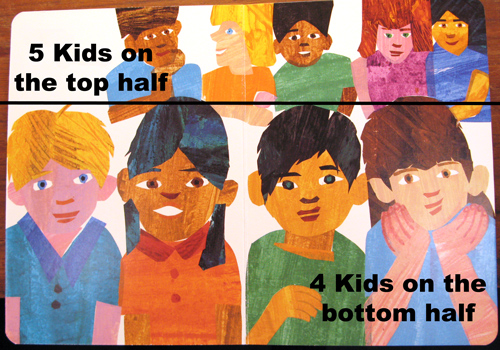

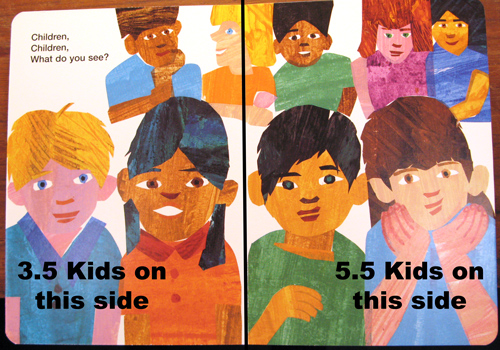

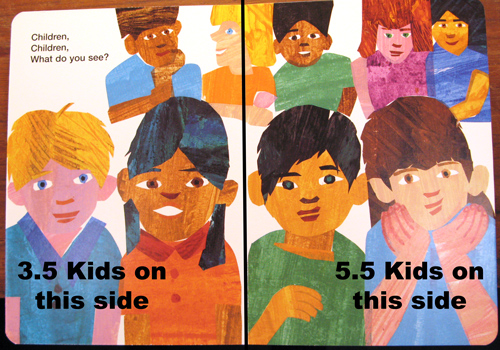

Visual processing is the ability to see and manipulate visual stimuli.

Visual processing is helpful to see shape, size, and relationships. We use it to see groups, understand angles, and other activities in math.

Quick matching of similar shapes or numbers is helpful here. You can make small tweaks to this activity by sorting by size with various sizes presented and the same for the orientation of the shape – a triangle upside down or at an angle matching a triangle presented in the vertical position.

Logic and reasoning allows us to see patterns and trends.

It allows us to order events. You need logic and reasoning to understand bigger concepts. When we decide what’s needed and how to set up a story problem we’re using logic and reasoning.

Practice copying patterns with young children using such items as beads or blocks. You can even have fun and have them create a pattern for a crown, flower pot border or placemat for dinner.

For older children, start a pattern and see if they can finish the pattern. This can be easily done with building blocks and Leggo’s ™.

Processing speed is how efficiently and quickly we can process information.

Processing speed is very important to be able to do the basics quickly and move to second or third steps.

To work on processing speed, try timing your child working his/her way through various paper and pencil mazes. Your child will love the competition when you make it a race between multiple participants!

Number fluency is recognition of written numbers.

Number fluency is a coding process normally developed by age three or four. If we are delayed with recognition of numbers, it slows us down with calculation.

You need two decks of cards for this fun task. Deal out one deck of cards, an equal amount of cards for each player. Use the second deck to flip the target cards over.

The players must match the number on the card, being pulled from the second deck. The first person to get rid of all their cards by matching the numbers is the winner.

To push number fluency that is more than visual recognition, have the participants say the number before they place their card on the target card and then the game moves on.

Conclusion

Knowing your child’s unique cognitive profile will help you understand their performance and take you one step closer to solving their math challenges.

The good news is weak cognitive skills can improve if targeted and trained. Brain training is a type of mental exercise, carefully designed to stimulate the brain and make lasting changes in cognitive abilities.

The idea is to improve one’s ability to learn, rather than focusing on one concept of math. It is analogous to learning how to play an instrument (which is a process) and not just a specific song (which is knowledge or data – one concept).

Vicki Parker, Ph.D. is the founder and director of The Brain Trainer and writes for their blog.