Equality is a big part of learning math. The equals sign means more than just “here’s the answer.” This is the second in a series on equality and comparison. For the rest of the series, click here.

It’s part of our DNA to assess the world around us. As soon as a baby sees Mommy different from Daddy (or smells the difference), she starts comparing. When she figures out that there are more than one of something, things get even more interesting.

Give each of two toddlers a ball. Then stand back and watch. If they aren’t exactly the same ball, one of them will want to switch, and the other will say no. It won’t matter which ball is truly superior, only that one child will soon perceive inequity in ball ownership.

If they are given the same color and size ball, you can watch their little brains calculate this and work to discern some difference.

And it doesn’t stop at kids. Women do it all the time. Is my bottom as big as hers? Do we wear the same size shoes (and will she let me borrow hers if we do)? Is my dress more expensive than her dress?

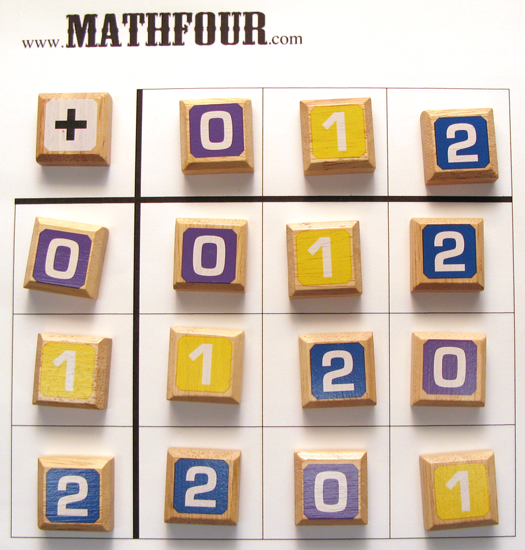

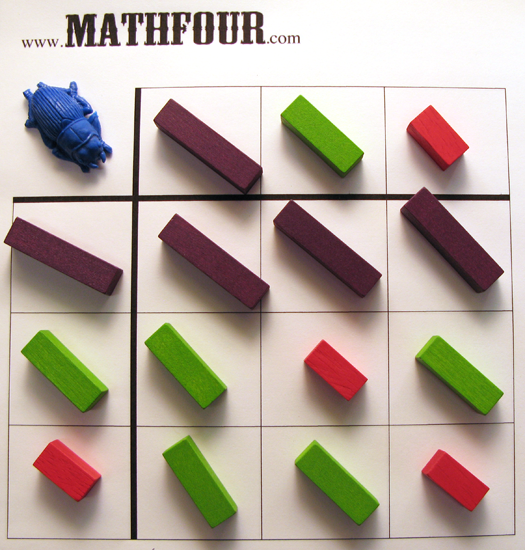

Comparison in math corresponds to comparison in the world.

Some things are really exactly the same.

Your two crystal champagne flutes you bought for your wedding are likely the same. Not only is one interchangeable with the other, but you couldn’t tell the difference if you were to switch them.

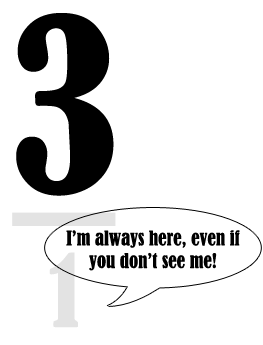

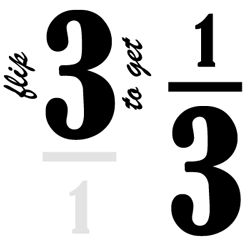

This can get a little sticky for math. There is only one number 3.

But when I write 3 = 3, there are really 2 threes running around. (Math friends: I realize two champagne flutes are not the same as two number 3s. But making analogies in the real world is tough if you don’t take a little poetic license.)

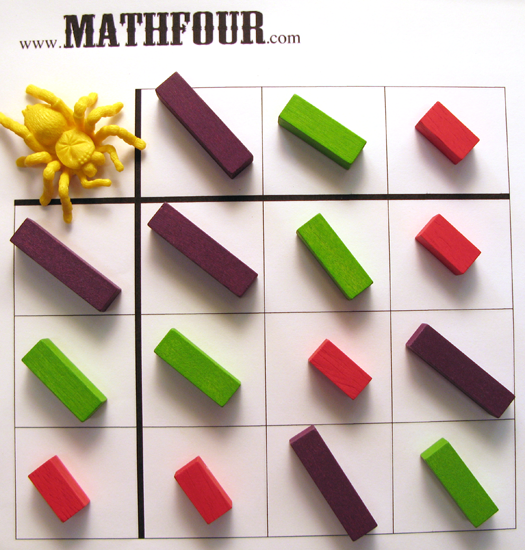

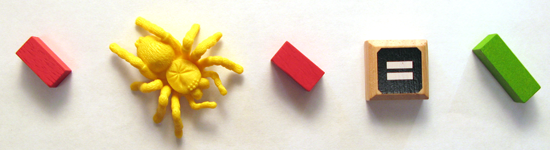

Sometimes things have the same value.

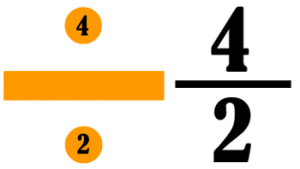

Have you ever traded a dollar bill for 4 quarters? Those aren’t exactly the same (you would be able to tell the difference if you replace one with the other) but they have the same value.

If you return a blouse to a department store that your weird uncle Zeno gave you, and get a blouse that fits your style much better, these will have the same value. Monetarily speaking, of course.

If you ship your G7 back to Canon when it’s under warranty, and they return a G10, the value to them was equivalent (while the value to you has increased).

Some things have the same size and shape.

When you replace the transmission in your car, you’re doing so with an equivalent copy that’s better than what you already have. If you replace the engine in your 1969 Mustang with a souped-up model, you’re playing the same game.

In both these situations, the replacement version, although superior in functionality, is the same in size and shape.

Sometimes things are interchangeable.

Like in the example above, with the cars, as long as one thing works equally as well as the other, you can compare them and call them “equal.”

If you reach for a pen from the pen jar on your desk, any pen will work as well as any other.

The two pens may not be exactly the same, have the same value or even be the same size and shape. But you can interchange one for the other when writing a check.

And sometimes equality is merely perceived.

Like the toddlers with the balls from above. Different people will put different value judgments on items. So there is the case that equality is in the eye of the holder. Or wanter.

What does equality mean to you?

As we progress through this series, we’ll see how equality and the equals sign in mathematics relate to equality in the real world. And thinking about how equality in the real world works is the first step.

So what do you think of when you think about two things being equal? Share your thoughts in the comments.