To mix things up a little, this month’s Math Teachers at Play Blog Carnival is a love story – between two people and then their new cute daughter. It’s a story of the coolest carnival of all – having kids.

The Story of Bernice and John, Mathematician Parents

by Bernice Abel

When John and I decided to have children, I knew we would be Making More Math Geeks. And I was okay with that. I was actually quite excited about it.

“How many kids do you want?” he asked before we were married. I thought about it a bit and said, “I probably want an odd number of kids.”

“What base is that in?” He asked me. I swooned. Could it be that he knew about Odd Numbers in Odd Bases? One thing was for sure, I knew he was Asking Good Questions. Especially when he asked me to marry him!

“You know,” he said, “We should have just the right number of girls and just the right number of boys. The Golden Ratio of our own, so to speak.”

There were so many things to be in love with in this man!

The day daughter was born was a life scalar multiple.

When I went into labor, I had just finished some Mathematics Crosswords and started an article called, “Curriculum Choice Review: Key to…Math Curriculum.” We raced to the hospital just in time for our sweet daughter, Clementine, to be born.

I immediately asked for pizza.

“Why pizza?” He asked.

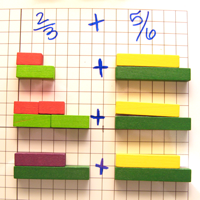

“I don’t know,” I said, “I just gave birth to a math geek, so I’m feeling like I should be eating 1/8, 1/4, or even 1/2 of something. I really don’t want our new daughter needing Fraction Help. And I know this hospital has pizza cut into 8 slices.”

He said, “You know, The (Mathematical) Trouble with Pizza is…” And then I glared at him. “Get me some pizza!” I screamed. The love of a math guy was wearing off.

“What took you so long?” I asked when he finally got back with my pizza. “You didn’t have to calculate any tip, and even My New Percent Lessons wouldn’t have helped you figure out the tax – the cash register does it all!”

“I was Actually Doing Day One Airplanes,” he said.

“What does that mean?” I replied.

“You know,” he said, “A little Math and Fun.”

I said, “My idea of math and fun is some Tesseracts and Factor Lattices. And I didn’t have either to keep me entertained while you were gone.”

I didn’t mention my desire for a iPad even though I had heard of the new fad of iPad Gaming in Math and Science. Money was tight and Clementine was already proving to be an expensive bundle of cuteness.

“Don’t even act like you were sitting around bored. You surely were writing some math ed thing like, 5 Tips For Coaxing Dreaded Maths Corrections From Your Child.”

He knows me so well!

![[50 Word Friday] The Original Flipped Classroom](https://mathfour.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-199.png)