The comparison of numeracy to literacy is curious.

Learning math is the opposite of learning to read. When you read, usually simultaneous to learning a language, you sound out words and then put meaning to them. When you learn to count and do math, you know the meaning inherently and then put a language to it.

At some point we learn to recognize words without sounding them out. And at some point we learn to recognize quantities without counting them out. This is called subitizing.

The Your Baby Can Read program uses the concept of subitizing to teach reading – you show your baby the word alongside the object. So the shape of the word car is as recognizable as a car itself.

The children using Your Baby Can Read don’t learn to sound out words. They don’t understand the concept of letters any more than babies not using the program. But they instantly recognize the shapes of the words – giving them an (assumed) advantage.

Aside: We didn’t use the “Your Baby Can Read” program, not because it was gimmicky (I love anything that looks gimmicky), but because there is a huge DVD element to it. We decided not to put Daughter in front of the TV for her first 2 years. A decision we stuck with, but sometimes was a struggle!

This article contains a “your baby can count” type program. (And it’s a free download!)

How did we learn subitizing?

I don’t recall having been taught it directly. Although I could be wrong. The research on it has been happening since the early 1900s, so it might have been taught without being labeled “subitzing.”

In a previous article about why learning to subitize is important, Christine Guest commented that she learned it out of frustration for counting with chanting.

I wonder how many of us do that. Are grownups so adept at subitizing that they forget that’s how we assess quantity? Maybe we’re taught to chant-count because that’s the way we think counting is.

But it isn’t!

How do you teach subitizing?

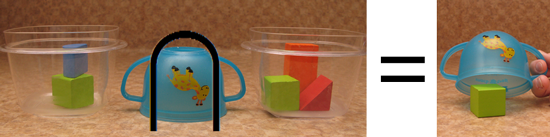

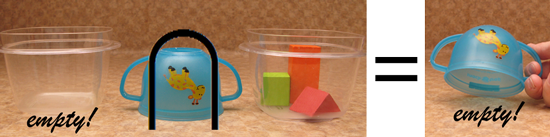

Images are accompanied by the written numeral as well as the number spoken aloud. The images would be printed on cards, done via video or “live” with 3D objects.

I’m still working on the numbers 5-10 and up, but for the numbers 1-4, the following 8 styles of image sets would be done twice. Once using the same objects for each image set, and once using different objects for each image set.

- Organized in a row vertically.

- Organized in a row horizontally.

- Organized in a row diagonally.

- Organized in a row other way diagonally.

- Organized in a regular shape (triangle, square).

- Organized in a differently oriented regular shape.

- Organized in an irregular shape.

- Organized in a different irregular shape. (There will be more of these for 4 than 3, etc.)

The objects could be blocks, cars, little dolls, just about anything. I created the set below from blocks I found left in Daughter’s block set.

Each zip file contains a few .jpg files with 4″ x 6″ pictures. You can print them at home or ship them to Walmart, Target, CVS, etc. for printing. I left off the MathFour.com logo so the kiddos wouldn’t get distracted. Please share them along with links back here.

What do you think? Can you use these? Did you?