I’ve been itching to get into some basic abstract algebra goodies. With the help of the Cuisenaire Rods, Simply Fun Sumology number tiles and the Discovery Toys Busy Bugs, I’m able to do that.

Start with wrap around addition.

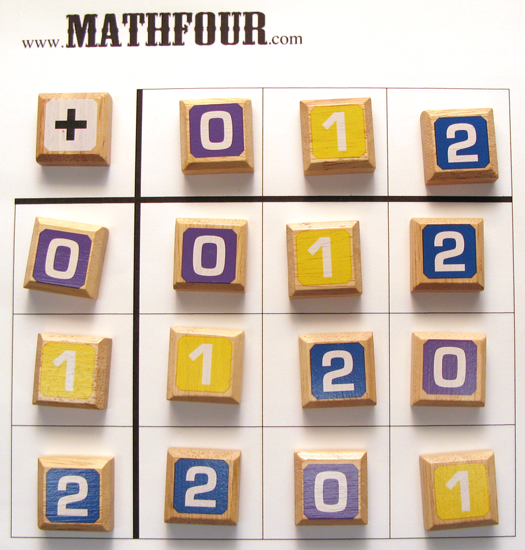

This type of math is officially called “modular arithmetic.” We are only going to use the numbers 0, 1 and 2.

It begins as regular addition. And since we are only using those three numbers, all our answers have to be either 0, 1 or 2. So when we add 1+2, we wrap around.

If we were to count in our system, we’d say: “0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, …”

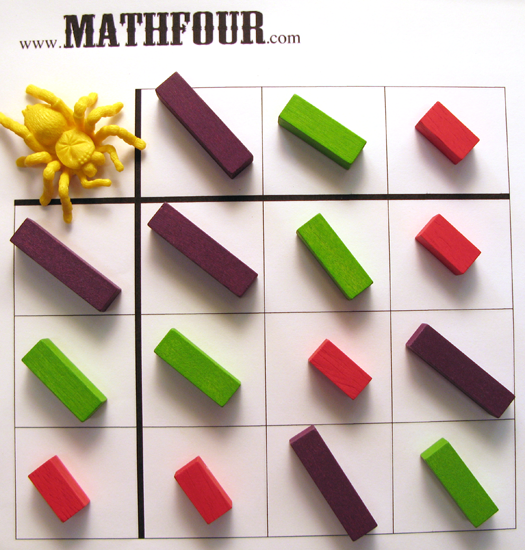

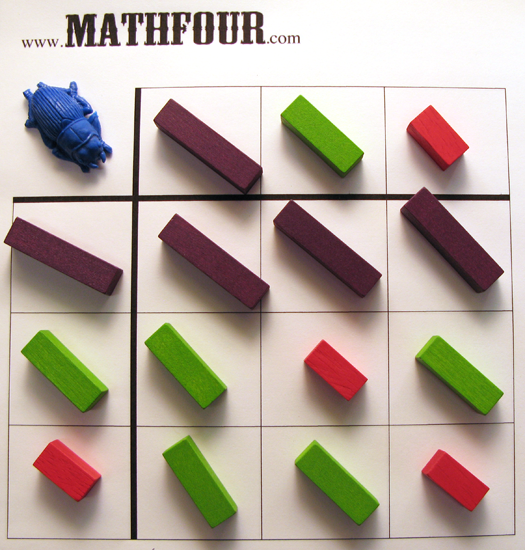

The addition table looks like this:

(Notice you could do this with numbers from 1- 12 and it would be clock addition!)

Now things get buggy.

Switch out all the number tiles with some pretty color Cuisenaire Rods. They don’t have to be the “right” rods. We’re only looking at the colors. Here’s the progression I did:

The end result is a very abstract chart!

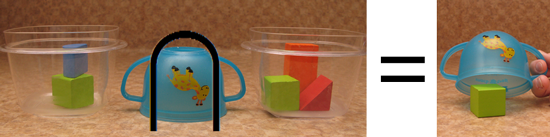

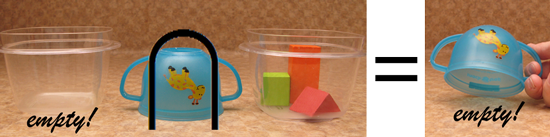

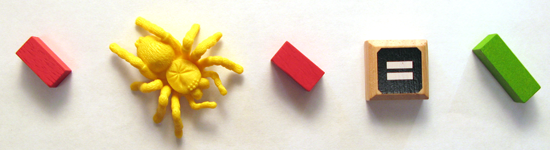

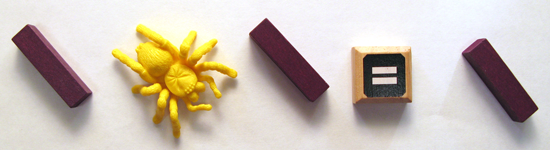

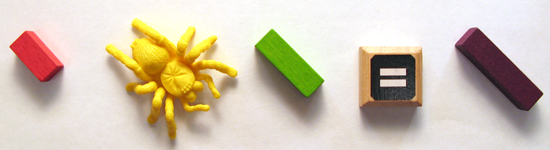

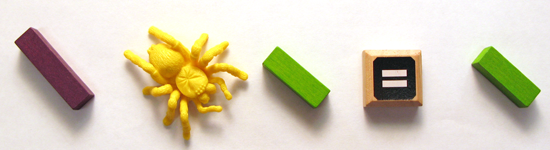

You can “bug” two things together.

Like this:

(I know – a spider isn’t a bug. But run with me on this, okay?)

Notice that each of these are directly from the “spider table” above.

You can read this as, “Purple spider green equals green,” just like you would say, “Zero plus one equals one.”

And then turn your child loose!

First make a chart, or download this one.

You can, but don’t have to, start out with numbers. The rules are this:

- You can only use three colors.

- All three colors must go across the top.

- All three colors must go down the left.

- Fill in the 9 spaces however you want, as long as it’s only those three colors.

I did this one with the blue beetle as the “addition” piece:

So what can you do with a goofy “blue beetle table”?

Let your child play, for one. And experiment.

You can also talk about commutativity and associativity, identities, inverses… but I’ll leave that for another article!

What do you think? Does your child want to play like this? What else can you do? Share your thoughts in the comments.