Most parents aren’t professional mathematicians. But there are a few. This is the sixth in a series of interviews with mathematician parents with the goal of helping parents integrate math teaching into parenting.

This week we visit with a high school math teacher in Mississippi. Jennifer Wilson, NBCT, teaches at Northwest Rankin High School, and is a Teachers Teaching with Technology (T3) instructor with Texas Instruments.

MathFour: Thanks so much, Jennifer for giving us your time. First, can you share a little about your degree and career?

Jennifer: I have a B.S. and an M.S. in mathematics. I have been teaching high school mathematics for 18 years.

MathFour: Tell me about your family – how many kids do you have and how old are they? Are any of them more or less interested in math than the others in the family?

Jennifer: I have two daughters who are 6 and 9. They are okay with math – but the 9 year old will tell everyone very quickly that her first love is reading.

MathFour: Do you have any worries about your girls academically? In particular, do you think they will do better in math than in other subjects because of your influence?

Jennifer: I feel very lucky to not be worried about my children academically. They love to learn. My husband and I both encourage their curiosity and try not to stifle their desire to ask why or come up with a different idea of how to do something, especially when the only good reason we can think of is “because I told you so”.

I think they will do well in math – but not necessarily better than other subjects. My husband and I both love to learn, and so the girls definitely recognize that desire and enjoy learning as well.

MathFour: That’s great! How do you play with your daughters? Do you view your playtime as different in any way than other “non-mathematician” parents?

Jennifer: We play games. I probably view play differently than a lot of parents – but probably similar to many teachers, no matter their subject of expertise. I am all about learning, and it is hard to turn that off, even at home.

MathFour: Do you think you speak with your daughters or behave differently than other parents because you have a math background?

Jennifer: Yes. Anytime some kind of math problem arises, I always ask the girls about their thinking, because I am very interested in how they arrive at answers.

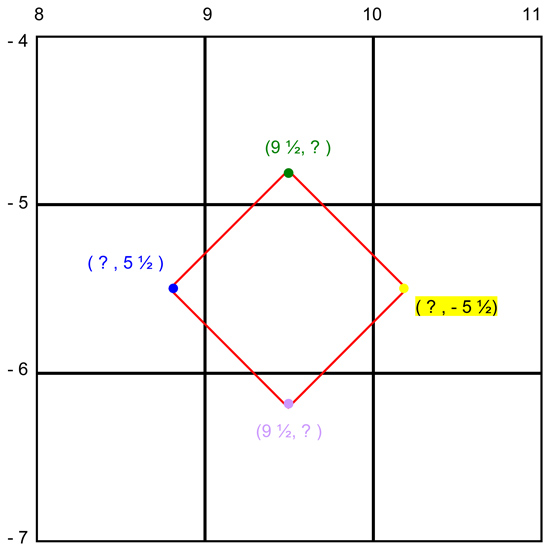

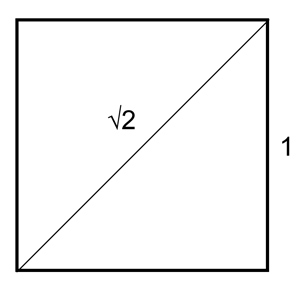

At dinner, one daughter noticed that her tortilla chip was in the shape of a trapezoid, so we had a great conversation that night about trapezoids. We have a “pi” pie plate, so both girls already know a little bit about pi. They definitely call an “oval” an ellipse and a “diamond” a rhombus. They have called their blocks by the appropriate solid names, such as cylinders, prisms, and pyramids, since a very early age.

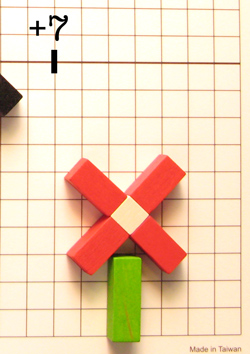

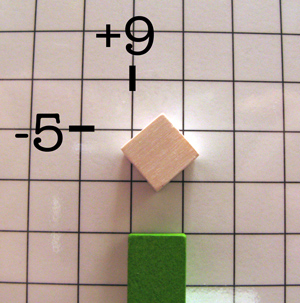

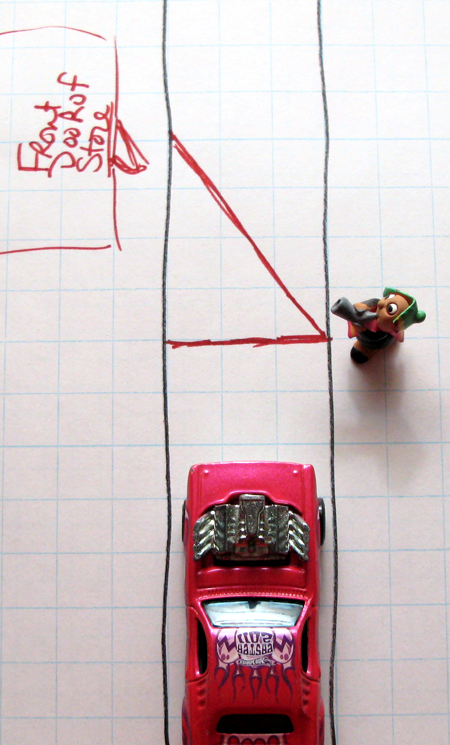

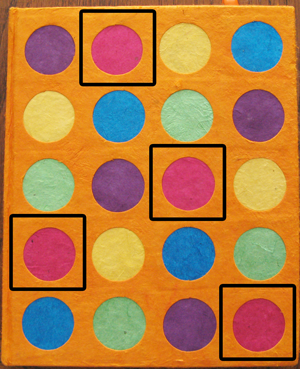

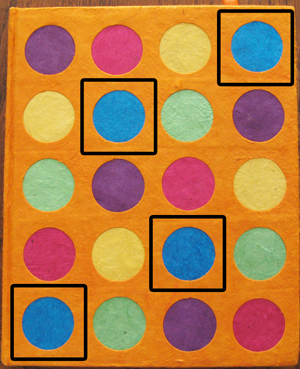

When the 9 year old missed a question on her state practice test about perspective drawing, instead of just telling her the correct answer, I got out the stash of Unifix cubes at our house to make her build the drawing with the cubes. She completely understood after doing so – and asked me to make up some more questions for her because she enjoyed working through the problems with the manipulatives. Both daughters play with my TI-Nspire™ CX handheld. They love making shapes, measuring their parts, and making them different colors.

MathFour: I had to google that one – fancy device!

Have you ever had either of your girls express negative thoughts about math? If not, how do you think you will handle it if that happens?

Jennifer: Not yet…I’m not sure I will handle it well. But I am hopeful that since my goal is not just calculating math but understanding math, they can at least appreciate my passion for it, and I will honor their passion for another subject, if the need arises.

MathFour: How do you think you’ll handle it if you find your self in disagreement with one of your children’s math teachers?

Jennifer: I’m not sure I will handle it well if it does happen, but so far, so good. I am lucky to teach in a great school district with great support for teachers at all levels, so I will keep my fingers crossed!

MathFour: Now to change direction a little to a more worldview of math. What do you see as the biggest challenge in math education today?

Jennifer: Having teachers who are experts in mathematics at all grade levels.

MathFour: What do you see great happening in the world of math education?

Jennifer: I see teachers who are willing to use technology to engage students in the learning and understanding of mathematics, teachers who are learning alongside students (often because of and through technology), and teachers who are willing to give up some of their control over the classroom to create a classroom that is truly interactive.

MathFour: What advice can you give to non-mathematician parents that might help them raise their kids to like and appreciate math.

Jennifer: I have been amazed at some of the mathematics that my students are learning in the computer games that they play. So while I realize that some students go overboard with the time that they spend in front of their electronic devices, find a way to encourage them to explore mathematics through tools that do interest them.

MathFour: Wonderful, Jennifer, thank you so much!

How ’bout You? It’s back to school time – do you have any questions for a super technology oriented math mom? Ask them in the comments!