I had this grand idea when we got married and were hoping for kids – I would teach our children to count starting at 0.

When Daughter was 15 months old, I decided we should start teaching to count with negatives.

But I was wrong on both.

And so is everyone else.

Why do we teach toddlers to count?

We practice counting 1-10 with our kids. We know (somehow) that before they’re official school age, they should know how to count to 10. And how proud we are as parents if they can count to 20!

But these are just words.

I can teach Daughter to memorize the Fibonacci sequence, but she’d no more know what that means than what counting to 10 means.

In fact, I know this first hand because I used to count to 10 in Spanish. And I’d leave out ocho everytime!

I saw a guy made fun of in Germany because he told a waitress he had fünf people in his party and held up four fingers. (She did it behind his back to another waitress – she wasn’t so rude to say it to his face. (Thank goodness; I would’ve had to go Texan on her.))

We teach toddlers to count for the same reason that we teach them to say please, thank you, yes ma’am and no ma’am – because someday they’ll understand what it means. And in the meantime they can establish good habits.

So where do they start understanding?

Regardless if we teach a toddler to start counting with -5, 0 or 1, they start with 2.

-5 to a toddler makes no sense. Teaching -5 to a toddler can only be dreamed up by a math teacher with no kids (i.e. me three years ago).

0 is useless. Why would you even mention that you have zero? Maybe saying that there are zero cookies after she ate them all might work. But generally zero things can’t be seen and by the time you’re down to 0 cookies, there’s probably a meltdown in the works. And we all know there’s no learning during a meltdown.

1 is just as useless. Why count things that are only one? They started with one mom, one dad, one dog, one couch, one bed, one bear,… Almost everything in their world is a single. The number “one” is just as useless to them as the words “the” or “a.”

But 2 is interesting!

Daughter was so amazed at the discovery that she had two SnackTraps. Not just the ordinary situation of a bowl of snacks but “TWO BOWLS!”

As soon as multiple copies of things are in her world, she takes note. If you’re an identical twin, the first time your child sees you with your twin might be traumatic. My best friend is the daughter of a twin and she tells horrors stories of this discovery.

This is an extreme, but consider all the pairs of things that kids can notice – two shoes (vs. only one that you can find when you’re freaking out and you’re late), two forks (when you’re begging for yours back from her because you’ve not eaten since breakfast), two cars (when you need to get in one and she insists on going in the other).

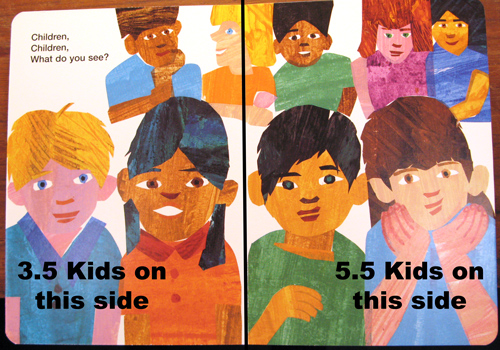

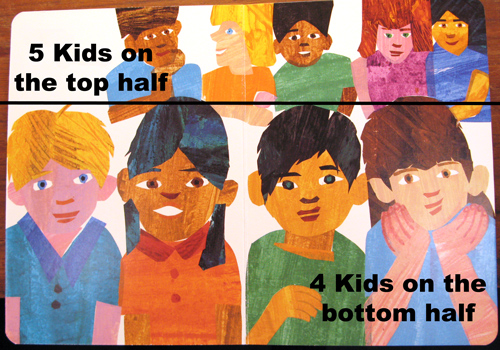

And, toddlers really don’t start counting at 2. They don’t start their mathematical careers with counting at all! They start by recognizing multiples. And 2 is the first and fastest multiple.

So what can you do?

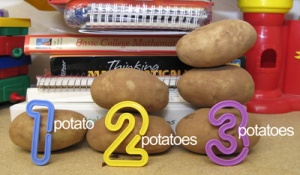

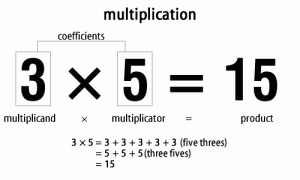

Keep teaching your kids to count – they still need this skill, just like they need to memorize math facts. But also teach them to subitize (recognize amounts without counting them out). Hold up two of the same items and exclaim “TWO ORANGES!” Then go to another two items and exclaim, “TWO RAISINS!” Stick with one number at a time.

Daughter is on “two,” so we’ll stick with that for a few months. We’ve got plenty of time.