This is the 6th and last in the series The Order of Operations Explained. For the other articles in this series, click here to visit the introduction.

I started this series over a month ago. In that time, I’ve gotten pretty deep in thinking, learning and reading about the order of operations. I’ve seen a variety of ways people view, use and teach it.

Before I go too far into some conclusions, though, let’s look at addition and subtraction.

Subtraction is the same as addition.

Yup. You might remember that from the fourth article.

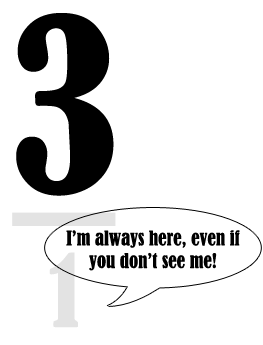

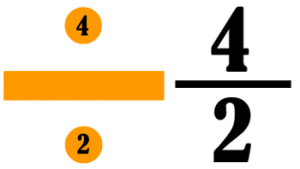

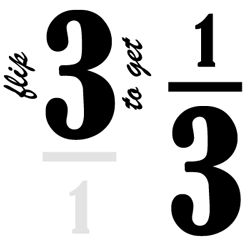

Consider the problem . Moving from left to right, and doing both subtraction and addition as we come to them, we get 4. If we found a book, or person, that meant the full-on PEMDAS and wanted addition done strictly before subtraction, then we would end up with 0. The latter is because we would do the addition of 3 and 2 before we did the subtraction.

Which is right?

It depends on what you really mean. If you don’t know if you should go left to right or strictly addition before subtraction, either look in the textbook you’re using or demand parenthesis.

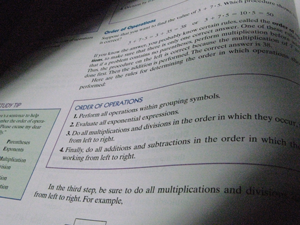

The text will clearly outline the order of operations it’s following. Be careful, too because there isn’t always agreement among textbooks. I have seen some texts that instruct the learner to do multiplication first and then go back and do all the division signs. While others (and this is more common, today) have us do multiplication and division from left to right, simultaneously.

If you compare contemporary texts to each other, you’re likely to find them all the same. But grab a math text from the 80s at Half Priced Books. I’ll bet you’ll find at least 50% of the time they put division strictly after multiplication. (I’ll verify this the next time I’m there.)

The order of operations needs context.

I have $5 in my bank account. Then I bought a coffee for $3 and a bagel for $2. I might accidentally write down . I still mean, “I need to add up the stuff I spent and subtract it from my balance.” I wrote it in error, though. What’s “mathematically” correct is .

But you knew what I meant.

This was a typo that was helped along by using the context.

Until there’s a reason to do arithmetic, the order in which we do things is arbitrary. If we all agreed to do addition first, then multiplication, we would calculate and come up with 35 (instead of 23).

As long as we all come up with the same thing, we’re fine.

“We” have agreed to do multiplication things before we do addition things. So “we” would come up with 23 in the example.

Coach G noted it correctly: the order of operations is a convention. In other words, we’ve decided on it. We invented it.

How can you use this to teach your children?

The coolest thing is that you can let them play. Get dirty. Break it.

Remember opposite day? Have that. Let your little one make new rules. Let them see what happens if you all decide one day to do multiplication before addition. If your child is older and doing some algebra, this will mean reversing the order in which you UNDO the operations too!

This is a real brain stretcher. But it’s just math. You’re not building a bridge or balancing your checkbook. Let them break it. Let them see what happens if you make your own rules.

And then they’ll really learn!

Let me know how it goes – share your stories in the comments.