If you’ve ever taught or tutored math you’ve encountered the question, “When am I ever going to use this?” Maybe even hundreds of times.

And no doubt you’ve tried the answers that you’ve heard your math teachers give:

- You’ll need it in a future job.

- You’ll want to balance your check book someday.

- Blah, blah, blah.

I was on the Teachers.net chatboard last night and there’s a discussion in the math teachers section about how to answer this question.

I was horrified to read that some teachers actually respond with, “How about as homework, you find the answer to that question.”

Egad!

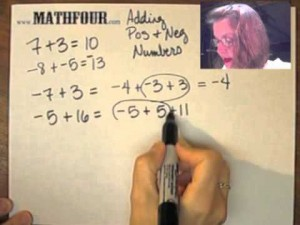

We all know it’s a discrationary tactic. We know that there are lots of good uses of math. And we’ve experienced our answers shot down with, “I’m not planning on doing a math job for a living, so I won’t need it,” or “I’ll hire a CPA to do my checkbook.”

There’s only one right answer to this question.

“You’ll never use the math I teach you. Ever.”

I offer $10 to anyone who can come back to me in 10 years and tell me that graphing functions (or whatever we are learning that day) has actually had an applicable use in their life.

Of course they’re horrified at this answer. They give me looks like, “What? Are you an alien here to invade our classroom. Did you eat the real Bon?” No teacher has ever been that honest.

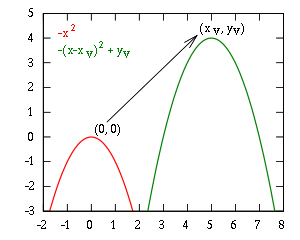

Graphing functions is virtually useless as a real tool. As is most of what we teach.

I used to get phone numbers from men at bars with my amazing use of the quadratic formula, but that’s only something you can tell college students. And they don’t buy it anyway.

Teaching math is teaching brain exercises.

The reason we teach and learn graphing functions (or other math) is to exercise a part of the brain that we rarely get to use. A part that will get used sometime later in a weird way.

We’re building new paths in the brain. We’re carving a way to alternative problem solving that might one day be useful in solving interpersonal, business, automotive, or other type of problems we have.

I tell them that math class is a game. A fun time to escape once a day. This is a play time to stretch their brains and do something completely different.

And I certainly don’t pile pissiness upon pissiness with the attitude of “If you’re going to challenge me, small menial student, then I’m going to give you extra homework.” That really motivates students… to hate math.

How about you? How do you answer the question? Are you supporting future math happiness? Share your thoughts in the comments.