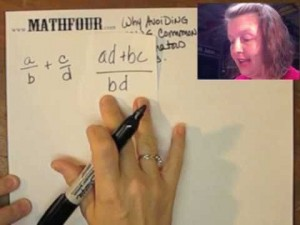

I did some videos for avoiding finding a common denominator and why this trick works. Ever since then I’ve pondered what it would look like if you added without a common denominator.

A mom on the Living Math forum was asking for advice on how to teach adding numerators and not adding denominators in fractions. So this topic is again in the front of my mind.

First note, that you can add both numerators and denominators – this is called piecewise addition – but then you are getting into a whole new world of stuff. Actually, you’ll be experimenting with some goodies from Abstract Algebra (my field of study). We’ll talk about how and why this is good in a few paragraphs.

What is adding fractions, anyway?

For us in the “real world,” adding fractions is adding values that can’t be counted with fingers. It’s adding bits of things together – maybe whole things with bits, even.

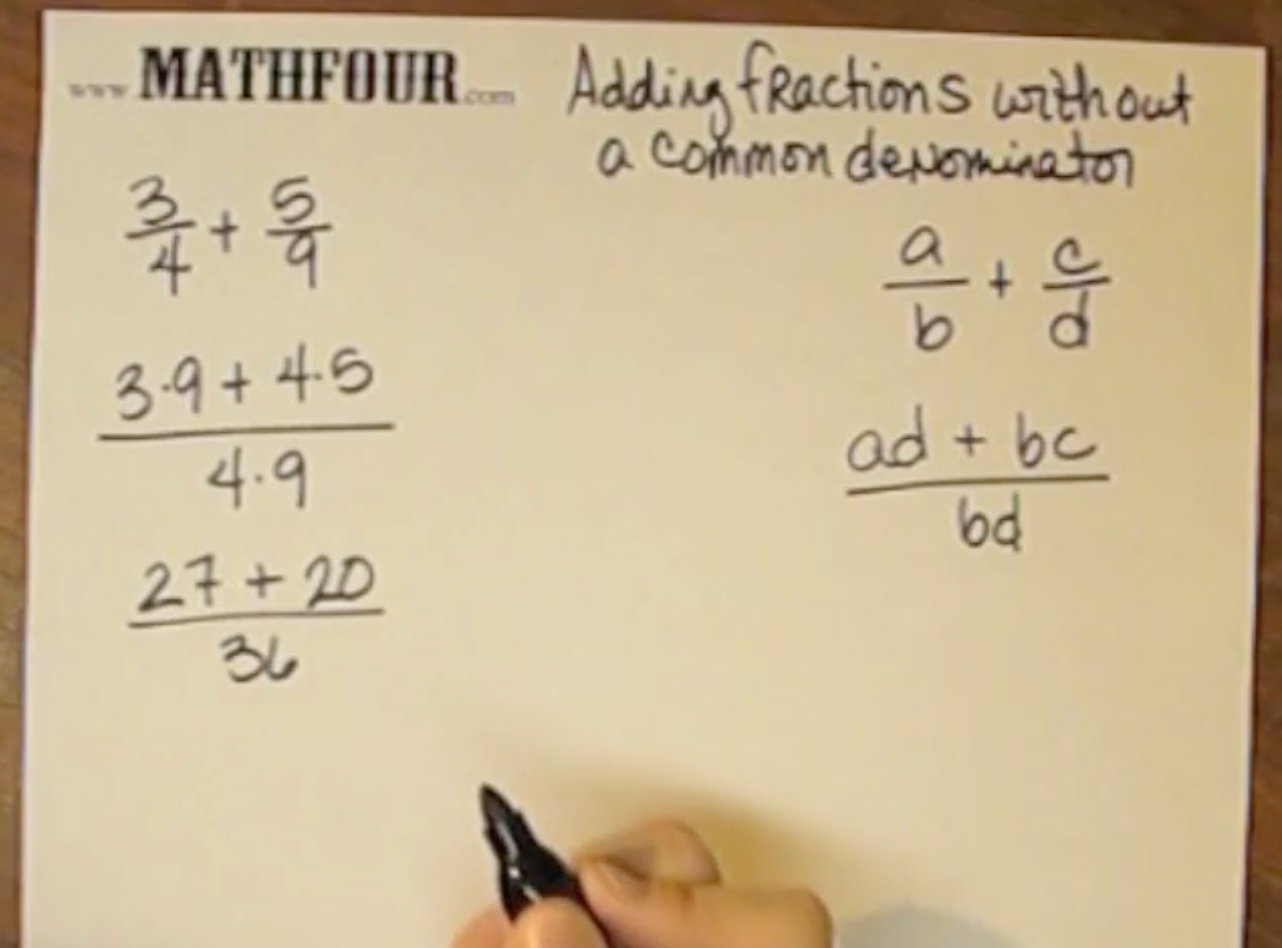

We have agreed to use things that look like

to represent fractional pieces of a whole.

When we add we have said that our total is

Quantity over value is important to young children.

I remember taking money from Little Brother when we were kids. You might think I was stealing, but it was more of conning the innocent. He would have 3 dollar-bills. I would have 20 pennies.

He would quite willingly trade his 3 monies for my 20 monies. For him, this was a matter of quantity. I knew the value, though. (Bad girl – sorry, LB I owe you. xo)

This measuring of quantity, rather than value was important in LB’s development. Instead of someone teaching him how to measure value, he learned it through experience.

This is why we should allow kids to add the denominators.

Let’s use the example above and add the numerators and the denominators to see what that means.

Adding means that our total is

Notice here you can’t “reduce” the fraction – because this isn’t the value as we know it.

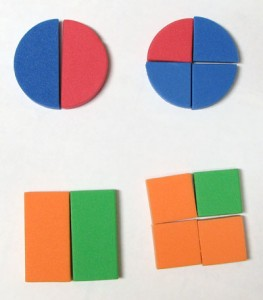

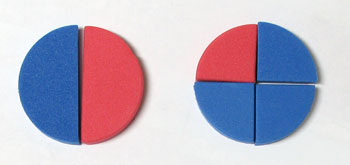

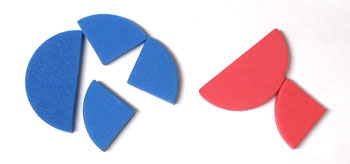

If you teach adding fractions using manipulatives or toys and allow adding denominators, soon your children will see that your (on the top in the picture below) is very different than having their , on the bottom.

This will inspire them to work toward equality – and invent fractional addition (correctly) on their own!

Tell us how it goes in the comments!