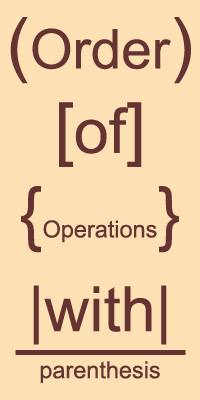

This is the 3rd in the series The Order of Operations Explained. For the other articles in this series, click here to visit the introduction.

Exponents are the second in the list for the Order of Operations (OoO).

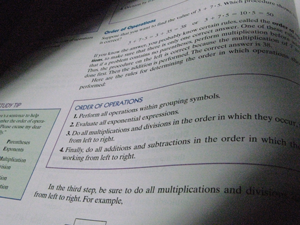

When we want to find the result of 32 x (2 + 7), we have no problem. We know to do parenthesis and then exponents, then multiplication.

When you teach algebra, you’ll have to teach some distributing of exponents. But that’s still okay. And the rules of exponents are pretty straight up.

So why a whole article on exponents?

In the order of operations, the “Exponents” rule represents a bunch more than just superscripts or tiny numbers flying up and to the right of things.

Roots are exponents, too!

Not the ones from trees, but things like square roots and cube roots. Consider . You do the square root first because it qualified as an “exponent.”

But if you had , the 9 + 2 is under the radical sign (the square root sign) so it’s bound together in the “Parenthesis” rule.

This one isn’t that hard with arithmetic, but when you come to algebra and start “undoing” these things – it’s important to remember that roots fall into this category.

Fractional exponents are exponents.

This one seems pretty “duh” so it’s easy to see how they fall into the “E” of the order of operations. But what are fractional exponents really?

So fractional exponents are the same as roots.

Note that some fractional exponents are roots and “plain” exponents all mixed up. Like this one:

This is a big fat full concept that needs a little more explaining. I’ll write more on these in another article.

Logs fall under the E.

As my algebra and computer math teacher in high school, Mrs. Kelley, used to tell us – logarithms are exponents. It took me a long time to figure out what the heck she meant. But when I did, I thought it was brilliant.

This is a true statement: . Let’s analyze it.

Based on the definition of logarithms, this means that 32 = 9. Which we know is true.

Notice who the exponent is in this: 32 = 9: 2 is the exponent. And 2 is the same as because the equals sign in means “is the same as.” So the logarithm is the exponent 2.

Still with me? Either way, it’s okay. It’s a weird concept that I can go into detail in a video soon.

The thing to remember here is that logarithms fall into the “Exponents” rule of the order of operations.

So if you have , you have to do the first and then add the 7 after.

Want more on exponents?

In the meantime, you can check out more than everything you always wanted to know about exponents on the Wikipedia Exponents page. Rebecca Zook created a great video on logarithms. And check out this explanation and problems to work on fractional exponents.

And let me know what you think. Did I miss something?